While we're more or less on the subject of fear, recent anti-immigrant hysteria has me thinking about all manner of historical precedents that show how effectively a crowd can be made to panic about something that has nothing to do with the actual threats to them.

Last year I traipsed through "The Party of Fear," a penetrating history of nativist/anti-immigrant crusades in America and their ties to wider right-wing movements. Seems that certain of our countrymen have been trying to bar the doors against more recent arrivals ever since Plymouth Rock changed hands. It's truly astounding to see how flexible and self-serving the definition of "real American" has been.

It's also illuminating to note that periods of anti-immigrant bias tend to coincide with economic downturns. People are anxious, angry and looking for someone to blame for their predicament, and swarthy people who talk all funny turn out to be an awfully convenient (and organizationally powerless) target.

I was also struck recently while watching "The History of the Devil," a fine little British documentary recently aired on public TV (and which Amazon lists as "starring Zoroaster," a casting coup if there ever was one) how depressingly familiar the descriptions of various anti-heretic crusades and witch purges sounded. Secret trials, pre-established guilt, ethnic stereotyping -- stop me if you've heard this one before.

The upshot, at least for me, is that it's a really useful practice, if someone is trying to make you afraid of something, to ponder a bit about what they might have to gain from this. An Anglican cleric in the devil documentary tartly makes the point that accusing one of being a Cathar, Templar or other variety of heretic was usually the medieval church's way of saying "What a nice estate you have."

In the case of anti-immigrant movements -- well, it is rather convenient for those in charge, especially the element that favors privileged treatment for the super-wealthy, to have a target for public anger other than the political and legal structures that have allowed such uneven distribution of wealth.

Critical thinking -- such a crazy idea it just might work.

Thursday, August 19, 2010

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

Tell us a story, Mr. Brain

We're all no doubt familiar with the sensation of fear undercutting rational thinking and response. Some stimulus triggers the willies, and suddenly your reactions become exaggerated well beyond what you'd consider normal for somebody else.

Psychologist Martha Stout, who helped make sense of a particular kind of senselessness with her alarming book "The Sociopath Next Door," gives a fascinating biological account of how fear short-circuits reason in her more recent "The Paranoia Switch."

Under normal circumstances, the hippocampus part of the brain acts as an efficient and wise traffic cop, integrating sensation with emotional input and assigning ordered reactions accordingly. The result is that after a normal-to-pleasant event, you can mentally reconstruct not just the event but the emotions associated with it. You can build a story, allowing the event to inform and enrich future interactions with the world.

If an event sets off your fear response, however, your hippocampus quickly gets overwhelmed with the urgent emotional messages being broadcast by your limbic system. Memories of the event come together haphazardly and in fragments. "They remain in the brain as incoherent memory traces and sensations, constituting a cruel little hair trigger, a paranoia switch."

When something happens that reminds of you of that traumatic event, you have no coherent story to guide your emotional reactions. Instead, you're stuck in that greatest of fear factories, the unknown, re-experiencing that original limbic tornado.

Fortunately, our brains don't stop at the hippocampus. We have that big ol' cortex, which allows us -- with a lot of practice, attention and effort -- to build reasonable, useful stories even around the nasty stuff.

Psychologist Martha Stout, who helped make sense of a particular kind of senselessness with her alarming book "The Sociopath Next Door," gives a fascinating biological account of how fear short-circuits reason in her more recent "The Paranoia Switch."

Under normal circumstances, the hippocampus part of the brain acts as an efficient and wise traffic cop, integrating sensation with emotional input and assigning ordered reactions accordingly. The result is that after a normal-to-pleasant event, you can mentally reconstruct not just the event but the emotions associated with it. You can build a story, allowing the event to inform and enrich future interactions with the world.

If an event sets off your fear response, however, your hippocampus quickly gets overwhelmed with the urgent emotional messages being broadcast by your limbic system. Memories of the event come together haphazardly and in fragments. "They remain in the brain as incoherent memory traces and sensations, constituting a cruel little hair trigger, a paranoia switch."

When something happens that reminds of you of that traumatic event, you have no coherent story to guide your emotional reactions. Instead, you're stuck in that greatest of fear factories, the unknown, re-experiencing that original limbic tornado.

Fortunately, our brains don't stop at the hippocampus. We have that big ol' cortex, which allows us -- with a lot of practice, attention and effort -- to build reasonable, useful stories even around the nasty stuff.

Monday, August 9, 2010

The past is past

One of the things I particularly like about the life coaching program at UCSF (which I'm a few courses from finishing) is that they put a lot of emphasis on positive psychology, a new movement within the healing arts that's gaining a lot of attention.

One of the most striking tenets, particularly for anyone with some background in traditional psychology, is that it's generally not all that helpful to dig around for the root causes of an unwanted behavior.

For anyone invested in the old paradigm, this is darn near heretical. Not spend hours digging into one's childhood, trying to resurrect hidden traumas and mis-learnings? How can you even call that psychology?

But the Freudian notion that uncovering the roots of a neurosis is akin to curing it has steadily lost credibility. Awareness is one thing. But getting rid of bothersome behaviors also requires diligent work to construct healthier replacement behaviors. Insight into the roots of the old behaviors isn't necessarily going to help in that endeavor, and it may hinder a person by keeping him trapped in the past.

"The promissory note that Freud and his followers wrote about childhood events determining the course of adult lives is worthless," Martin Seligman, the godfather of positive psychology, writes in his groundbreaking book "Authentic Happiness."

Seligman's prescription for improved mental hygiene is to focus on building positive behaviors and habits -- gratitude, optimism, savoring pleasures -- rather than devoting a lot of attention to the behaviors you want to lessen. You'll enjoy it more, and your healthy new behaviors will steal time from the old ones. In short, starve your neuroses rather than hunting them down and trying to club them to death.

Again, this may seem heretical to anyone who's had much to do with traditional psychology, but there's a lot to recommend the approach. For starters, it seems that a lot more people might be willing to give positive psychology a try than the old model. "Relive past traumas in full, gory detail!" is a hard idea to sell. "Practice being happy" would seem to have much better legs, marketing-wise.

And it seems one would be much more likely to stick with a process that focuses on exploiting and developing one's strengths, as positive psychology promotes, rather calling attention to deficiencies.

Further, most of the arguments against positive psychology boil down to naive and puritanical variations on "No pain, no gain." Fine, maybe, for a masochist. But, notwithstanding my Lutheran upbringing, I'm a firm believer that there's no inherent virtue in doing something the hard way. Sometimes, hard is just hard.

One of the most striking tenets, particularly for anyone with some background in traditional psychology, is that it's generally not all that helpful to dig around for the root causes of an unwanted behavior.

For anyone invested in the old paradigm, this is darn near heretical. Not spend hours digging into one's childhood, trying to resurrect hidden traumas and mis-learnings? How can you even call that psychology?

But the Freudian notion that uncovering the roots of a neurosis is akin to curing it has steadily lost credibility. Awareness is one thing. But getting rid of bothersome behaviors also requires diligent work to construct healthier replacement behaviors. Insight into the roots of the old behaviors isn't necessarily going to help in that endeavor, and it may hinder a person by keeping him trapped in the past.

"The promissory note that Freud and his followers wrote about childhood events determining the course of adult lives is worthless," Martin Seligman, the godfather of positive psychology, writes in his groundbreaking book "Authentic Happiness."

Seligman's prescription for improved mental hygiene is to focus on building positive behaviors and habits -- gratitude, optimism, savoring pleasures -- rather than devoting a lot of attention to the behaviors you want to lessen. You'll enjoy it more, and your healthy new behaviors will steal time from the old ones. In short, starve your neuroses rather than hunting them down and trying to club them to death.

Again, this may seem heretical to anyone who's had much to do with traditional psychology, but there's a lot to recommend the approach. For starters, it seems that a lot more people might be willing to give positive psychology a try than the old model. "Relive past traumas in full, gory detail!" is a hard idea to sell. "Practice being happy" would seem to have much better legs, marketing-wise.

And it seems one would be much more likely to stick with a process that focuses on exploiting and developing one's strengths, as positive psychology promotes, rather calling attention to deficiencies.

Further, most of the arguments against positive psychology boil down to naive and puritanical variations on "No pain, no gain." Fine, maybe, for a masochist. But, notwithstanding my Lutheran upbringing, I'm a firm believer that there's no inherent virtue in doing something the hard way. Sometimes, hard is just hard.

Friday, August 6, 2010

Just words?

One of the key ideas/techniques in most cognitive work is learning how to identify unhelpful and inaccurate thoughts and replace them with statements that work better for you and happen to also accord better with reality.

"It's hopeless," for example, is an unhelpful (it discourages you from doing anything) and incorrect (making absolute predictions about the future), albeit familiar, thought/feeling. Thinking about it, one might decide that "Things are tough now, but I've dealt OK with similar crises before and I have a lot of resources" serves one better.

One of my favorite parts of Albert Ellis' "A New Guide to Rational Living," one of the foundations of cognitive psychology, is where Ellis anticipates a common objection to such mental work. "But it's just semantics," the skeptic might argue. "You're just playing with words."

Exactly, Ellis responds. But please drop the "just."

Because words are everything. As uniquely verbal creatures, we think in words. Our thoughts guide our emotions. So if you want to use your thoughts to changes your emotions, semantics is the tool set you're going to have to work with. "By the time we reach adulthood, (we) seem to do most of our important thinking, and consequently our emoting, in terms of self-talk or internalized sentences," Ellis writes.

So how better to reshape a one's emotional life than start playing with those sentences?

Perhaps this is a position that appeals to my biases as someone who's spent 30 years tangling with words for a living. But I still can't think of a better way to get the big brain talking with the lizard brain.

"It's hopeless," for example, is an unhelpful (it discourages you from doing anything) and incorrect (making absolute predictions about the future), albeit familiar, thought/feeling. Thinking about it, one might decide that "Things are tough now, but I've dealt OK with similar crises before and I have a lot of resources" serves one better.

One of my favorite parts of Albert Ellis' "A New Guide to Rational Living," one of the foundations of cognitive psychology, is where Ellis anticipates a common objection to such mental work. "But it's just semantics," the skeptic might argue. "You're just playing with words."

Exactly, Ellis responds. But please drop the "just."

Because words are everything. As uniquely verbal creatures, we think in words. Our thoughts guide our emotions. So if you want to use your thoughts to changes your emotions, semantics is the tool set you're going to have to work with. "By the time we reach adulthood, (we) seem to do most of our important thinking, and consequently our emoting, in terms of self-talk or internalized sentences," Ellis writes.

So how better to reshape a one's emotional life than start playing with those sentences?

Perhaps this is a position that appeals to my biases as someone who's spent 30 years tangling with words for a living. But I still can't think of a better way to get the big brain talking with the lizard brain.

Monday, August 2, 2010

Consider the source

For many years, my computer monitor has been adorned with one of my favorite quotes relating to emotional life, mental well-being, etc:

Recently, however, it has come to my attention that the phrase actually has little, if anything, to do with Hafiz. It is from Daniel Ladinsky, by most reckoning a minor British poet who had the marketing sense to hitch his fortunes to Hafiz and a growing interest in Sufi mysticism.

The cover of "The Gift ," in which the line I so like appears, labels the work as "Poems by Hafiz, the great Sufi master. Translations by Daniel Ladinsky."

," in which the line I so like appears, labels the work as "Poems by Hafiz, the great Sufi master. Translations by Daniel Ladinsky."

The writer is coyer in the introduction, saying his poems are "renderings" of Hafiz works meant to capture the spirit of the originals for modern readers. Further inquiry reveals Ladinsky neither speaks nor reads Persian, making his qualifications dubious for any normal conception of "translator."

Further reading of more scholarly interpretations of Hafiz's work reveal a tight formal structure that bears no resemblance to the free verse of "The Gift."

Which leaves me in a quandary. I still love that quote. But it's one thing to pass along the wisdom of Hafiz and quite another to quote "this British guy who kind of..."

Should that matter to me? Or should one accept wisdom wherever one finds it?

"Fear is the cheapest room in the house. I would like to see you living in better conditions."All along, that line has been attributed to Hafiz, the mystic poet of 14th century Iran who wrote movingly about love, God and wine.

Recently, however, it has come to my attention that the phrase actually has little, if anything, to do with Hafiz. It is from Daniel Ladinsky, by most reckoning a minor British poet who had the marketing sense to hitch his fortunes to Hafiz and a growing interest in Sufi mysticism.

The cover of "The Gift

The writer is coyer in the introduction, saying his poems are "renderings" of Hafiz works meant to capture the spirit of the originals for modern readers. Further inquiry reveals Ladinsky neither speaks nor reads Persian, making his qualifications dubious for any normal conception of "translator."

Further reading of more scholarly interpretations of Hafiz's work reveal a tight formal structure that bears no resemblance to the free verse of "The Gift."

Which leaves me in a quandary. I still love that quote. But it's one thing to pass along the wisdom of Hafiz and quite another to quote "this British guy who kind of..."

Should that matter to me? Or should one accept wisdom wherever one finds it?

Book report: "Traffic: Why We Drive the Way We Do (and What it Says About Us)"

There's a lot about engineering in Tom Vanderbilt's fascinating explanation of why driving sucks, but the most intriguing ideas are of a psychological/sociological nature.

Condensed version: Driving a car is a hugely complex task we're forced to accomplish with a vital piece equipment (your brain) designed for far more basic functions.

Vanderbilt covers topics such as distraction, the inherent narcissism in being a motorist (you're always the best driver on the road) and the phenomenon of risk compensation: Make a system safer, and people with use it in a riskier way that eventually cancels out any advantage.

For my money, the most captivating idea comes as Vanderbilt tries to explain our exaggerated emotional reactions to whatever happens on the highway. If someone cuts you off or makes an inopportune U-turn (quickly emerging as the top new thrill sport in San Francisco), you're likely to get mad and defensive all out of proportion to the actual risk posed by the behavior. Likewise, if another driver does you a courtesy, you'll feel good out of proportion to the significance of what in reality will be a very minor event in your day.

Vanderbilt's explanation is that our brains are wired to handle maybe 100 or so human relationships in a lifetime, reflecting the conditions when our ancestors lived in hunter-gatherer tribes. Back then, any encounter with another person had potential life-changing significance. "Thag scowl at me. Thag no like me. Thag burn down hut!"

Evolution being what it is, that's the basic brain we're still working with. Yes, your higher cortical functions can suss out the relative significance of events if you give it time. But in the moment, your reactions are dictated by a part of the brain that does not recognize the concept of a casual, meaningless social encounter.

Condensed version: Driving a car is a hugely complex task we're forced to accomplish with a vital piece equipment (your brain) designed for far more basic functions.

Vanderbilt covers topics such as distraction, the inherent narcissism in being a motorist (you're always the best driver on the road) and the phenomenon of risk compensation: Make a system safer, and people with use it in a riskier way that eventually cancels out any advantage.

For my money, the most captivating idea comes as Vanderbilt tries to explain our exaggerated emotional reactions to whatever happens on the highway. If someone cuts you off or makes an inopportune U-turn (quickly emerging as the top new thrill sport in San Francisco), you're likely to get mad and defensive all out of proportion to the actual risk posed by the behavior. Likewise, if another driver does you a courtesy, you'll feel good out of proportion to the significance of what in reality will be a very minor event in your day.

Vanderbilt's explanation is that our brains are wired to handle maybe 100 or so human relationships in a lifetime, reflecting the conditions when our ancestors lived in hunter-gatherer tribes. Back then, any encounter with another person had potential life-changing significance. "Thag scowl at me. Thag no like me. Thag burn down hut!"

Evolution being what it is, that's the basic brain we're still working with. Yes, your higher cortical functions can suss out the relative significance of events if you give it time. But in the moment, your reactions are dictated by a part of the brain that does not recognize the concept of a casual, meaningless social encounter.

Your jury-rigged brain

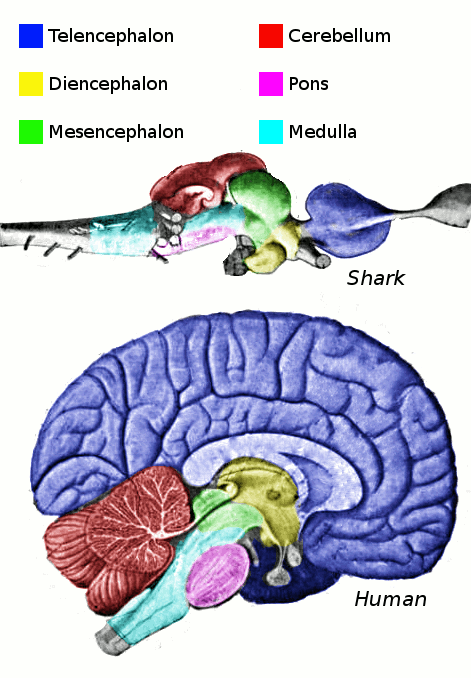

I was enjoying yet another lecture on neurology and brain function recently when I was struck by the plastic brain model used to illustrate the lesson.

I don't know if it was the construction, the way different brain segments were colored or what, but a somewhat familiar thought occurred to me with wholly new force: This is not a new brain. This is a basic mammal brain with a bunch of cortex glopped on top.

Now, any engineer will tell you that an old machine retrofitted to serve a new function never works as well as a machine designed specifically for that function. The re-jiggered machine will be big and clumsy, have redundant or useless parts, require complicated rewiring, etc..

Which is precisely what nature has gifted us with, noggin-wise. Yes, we have this big, nifty new cortex that can perform complicated math calculations, compose symphonies and cure polio. But we also have the old brain that evaluates everything strictly in threat/not threat terms, assumes ill intent just to be safe and treats every condition as permanent and irreversible.

And, given the way the parts are situated, the old brain always bats first. Yes, your cortex understands that the TV screen is showing a representation of a lion jumping at something, perfectly safe, notice the coloration on the tail. But in the time it has made those conclusions, the old brain has already made you jump and sweat with its message of "WE"RE GONNA DIE!"

A parable: When I was 10, I lobbied heavily for a new bicycle to replace the coaster-brake clunker I was outgrowing. Three-speed bikes were the norm at that point, and 10-speeds were gaining traction, so I made it clear to my Dad that I needed at least a three-speed model.

My Dad couldn't bear to get rid of anything that still worked, however, especially if it meant spending money for a replacement. Instead of a new bike, he found a Sears kit that supposedly turned a single-speed bike into a three-speed. Installed on my old bike with a few additional adjustments, he tried to sell me on the idea that I now had a brand new three-speeder.

But one ride around the block made the truth obvious to me: I had the same crappy bike, now with this ugly plastic tumor on the crank that played around with chain tension in a half-assed attempt to imitate an actual selection of gears.

And that, metaphorically, is what makes our mental lives so full and challenging. We're trying to navigate the complex, hilly terrain of a modern life full of symbols and ambiguities with the mental equivalent of a single-speed bike inherited from our ancestors.

Yes, we have all sort of dandy new systems bolted on to the old one. But sometimes the proof is in the ride.

I don't know if it was the construction, the way different brain segments were colored or what, but a somewhat familiar thought occurred to me with wholly new force: This is not a new brain. This is a basic mammal brain with a bunch of cortex glopped on top.

Now, any engineer will tell you that an old machine retrofitted to serve a new function never works as well as a machine designed specifically for that function. The re-jiggered machine will be big and clumsy, have redundant or useless parts, require complicated rewiring, etc..

Which is precisely what nature has gifted us with, noggin-wise. Yes, we have this big, nifty new cortex that can perform complicated math calculations, compose symphonies and cure polio. But we also have the old brain that evaluates everything strictly in threat/not threat terms, assumes ill intent just to be safe and treats every condition as permanent and irreversible.

And, given the way the parts are situated, the old brain always bats first. Yes, your cortex understands that the TV screen is showing a representation of a lion jumping at something, perfectly safe, notice the coloration on the tail. But in the time it has made those conclusions, the old brain has already made you jump and sweat with its message of "WE"RE GONNA DIE!"

A parable: When I was 10, I lobbied heavily for a new bicycle to replace the coaster-brake clunker I was outgrowing. Three-speed bikes were the norm at that point, and 10-speeds were gaining traction, so I made it clear to my Dad that I needed at least a three-speed model.

My Dad couldn't bear to get rid of anything that still worked, however, especially if it meant spending money for a replacement. Instead of a new bike, he found a Sears kit that supposedly turned a single-speed bike into a three-speed. Installed on my old bike with a few additional adjustments, he tried to sell me on the idea that I now had a brand new three-speeder.

But one ride around the block made the truth obvious to me: I had the same crappy bike, now with this ugly plastic tumor on the crank that played around with chain tension in a half-assed attempt to imitate an actual selection of gears.

And that, metaphorically, is what makes our mental lives so full and challenging. We're trying to navigate the complex, hilly terrain of a modern life full of symbols and ambiguities with the mental equivalent of a single-speed bike inherited from our ancestors.

Yes, we have all sort of dandy new systems bolted on to the old one. But sometimes the proof is in the ride.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)